Since FTP isn’t a standard archaeology project, much less a typical community archaeology project, many people ask us questions about the how’s, why’s, what’s, who’s, and where’s of our research. Here are some Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) which provide basic idea of what we do while following the pots. Click on a question you would like answered, or simply scroll down and read through the most commonly posed queries:

Follow the Pots is a research project to investigate how and why people excavate, loot, sell, and collect pottery vessels from the 5,000 year old cemeteries sites of Bab adh-Dhra`, en-Naqa, and Fifa, located in southern Jordan. We are attempting to follow these pots from their graves to museums, educational institutions, shops, and peoples’ homes wherever we can find them. In following the pots, we hope to learn more about what people think about archaeology generally, and how people value the archaeology of prehistoric Jordan more specifically.

Archaeologists, especially historical archaeologists have been working with communities for years, but for those of us who work in prehistory it is a newer practice. An excellent example of groundbreaking work in public/community archaeology is at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey. Talking to people about their interactions with the Early Bronze Age objects and landscapes is integral to a holistic approach to understanding the archaeology of the region.

It has been an eye-opening experience for us – when we started this research, we were amazed to find that people love to talk about themselves, their lives, their histories, and their places. As part of our research into local interactions with the landscapes of the dead we are interested in coming up with strategies that will allow people to connect with landscape in a way that doesn’t involve illegal digging and removing pots. We are trying to understand “why looting is important” – if it is a source of income, we, in collaboration with locals, want to think about how the landscape might generate a different kind of employment, perhaps through environmentally sustainable heritage tourism (for an example see the work of SCHEP).

In approaching our project, we first defer to the national Antiquities Laws (Law No. 21 1988 [2016 Amendments], Amending Law No. 23) in place in Jordan. Under Article 5 of Law No. 21 of 1988 “ownership of immovable antiquities shall be exclusively vested in the state”. But the question of “who owns the past” is more than just the legal definition, particularly when it comes to displaying, interpreting, and displaying the past. There is some urgency in examining this question due to the accelerated rate of destruction of archaeological sites and artifacts through unbridled development, illegal excavation, and a growing awareness that cultural heritage is an endangered non-renewable resource that must be protected and promoted for the general good of present and future generations. Beyond deferring to the law, we don’t really have an answer to this question, but we do try to take into consideration all those who claim to own the past.

Despite two governmental amnesty-buyback programs (Bisheh 2001; Politis 1994, 2002) local and foreign archaeologists and Jordanian government officials continue to struggle to stem the tide of looting. Making the connection between demand for artifacts and archaeological site destruction explicit is extremely important. By examining how both archaeologists and residents value and use these heritage resources, and by encouraging dialogue between area looters, non-looters, and archaeological officials, Follow the Pots recognizes that the way humans use material culture links to the past and to the present. We approach this difficult situation with empathy and openness to ensure that local voices are heard and realize that there are no “bad guys” in this scenario because all humans use and value material culture in many ways. Our goal lies in the application of our anthropological research to address the problem of looting on the southeastern Dead Sea, an activity which is entangled with poverty. It is hoped that the results of this research will provide the necessary data and grounding to assist in devising practical initiatives for ensuring that the area’s archaeological heritage resources are available for future generations, however they value the past.

The Early Bronze Age [EBA, see below for a FAQ on the EBA] pots we follow originally come from the archaeological sites of Fifa, Bab adh-Dhra`, and en-Naqa (also called es-Safi, the name of the modern Jordanian town) in the southern Ghor. The Ghor is the Jordanian name for the Jordan Valley, and extends from the southern end of the Sea of Galilee in the north to the northern end of the Wadi Arabah in the south, encompassing the Dead Sea Basin.

In this region, the largest communities are Mazraa (located about a kilometer west of EBA Bab adh-Dhra`), es-Safi (located adjacent to the EBA cemetery at en-Naqa) and Fifa (located next to the EBA cemetery at Fifa). Most of the locals we talk with live in one of these three towns, and many archaeologists have also lived in these towns sporadically while conducting research over the last several decades.

Most people who live in the southern Ghor make their living through agriculture or by working for the potash companies. There are also people who follow transhumant lifestyles, moving their herds (primarily of goats and sheep, but also of camels) and themselves according to the seasons from the below-sea level lands of the southern Ghor to the west onto the Kerak Plateau (at about 1000 meters above sea level).

Aside from the towns or villages of es-Safi, Mazraa, and Fifa, there are several well-known archaeological sites in the region, including the sugar mill (Tawahin es-Sukhar) adjacent to the ancient cemetery at en-Naqa, and Deir `Ain Abata (also known as Lot’s Cave). The Museum at the Lowest Place on Earth is situated on the lower slopes of the hill on which Deir `Ain Abata is located (for further information on the region see Zoara, the Southern Ghor of Jordan by Konstantinos D. Politis).

We are truly fascinated by what people think about archaeology and the associated material remains. Our research is guided by questions surrounding how people (local and foreign) connect with the landscape, the practice of archaeology, and the artifacts associated with ancient peoples. We are interested in how people relate to the past – if they think about ancient ancestors, archaeological landscapes, and artifacts. We use these pots, which are highly desirable collectibles, to track the interactions of archaeologists, collectors, government officials, looters, and museum professionals, with the archaeology of the southern Dead Sea Plain. We hope that by investigating the various lives of these pots we will be able to answer questions regarding archaeology, ancestors, landscapes, cultural heritage, and the present.

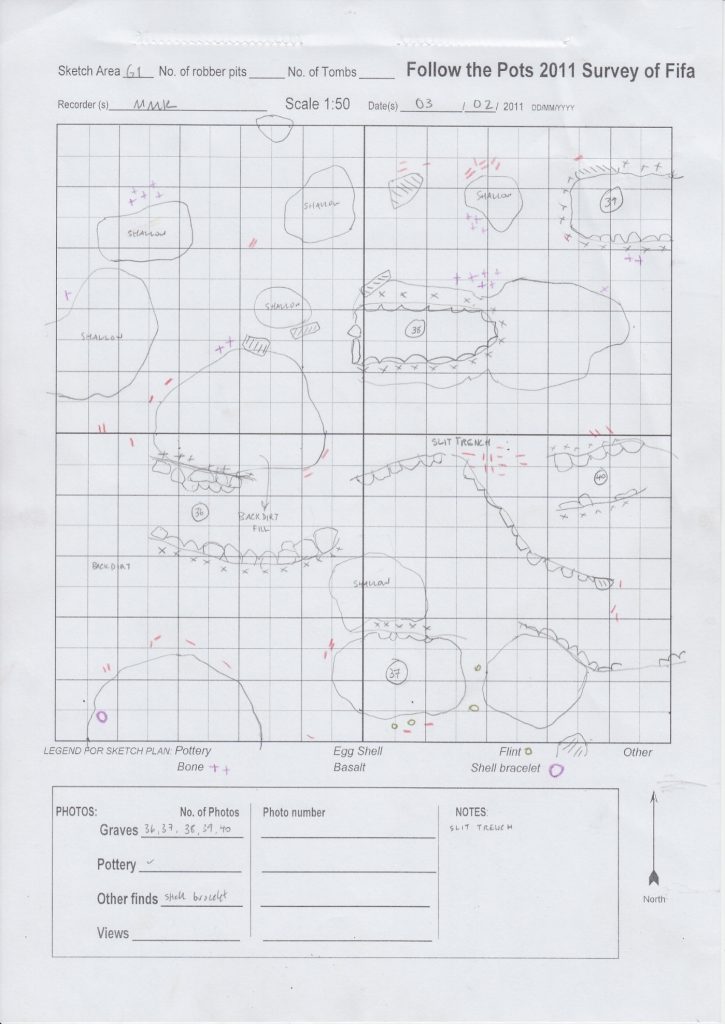

We combine both traditional archaeological methods (like mapping the site of Fifa) with ethnographic interviews with people.

Archaeological Methods

In January and February 2011 two archaeologists and one archaeological surveyor mapped the site of Fifa. Today the site resembles a moonscape, with looters’ holes extending across rolling hills as far as the eyes can see, and the ground is covered with the spoil heaps of dirt, skeletal remains, and broken artifacts. Such a scale of destruction makes total documentation of all looters’ pits impossible. Therefore, the team focused on recording the site in three different ways:

(1) The team produced a topographic map of the site, marking the boundaries of the cemetery as best as they can be determined by looking at materials on the surface. To produce this map, the surveyor used a Total Station, which is a computerized surveying instrument that records distances and elevations digitally, all of which can be downloaded to a mapping program on a computer.

(2) In addition to mapping the extent and topographic contours of the site, the team recorded the location of looted tombs across a portion of the cemetery. These looted tombs were marked onto the overall site map.

(3) The vast number of looter pits and looted tombs mean that it would be impossible to record all pits and tombs across the site. Therefore, the team set up ten intensive study units. Each study unit was 20 x 20 m in size. Each of these units can be seen on the site map, labeled A through J. In each of these units, the team recorded the location of all looter pits, looted tombs, spoil heaps, archaeological objects and human remains located on the surface. For each of these areas, they produced maps illustrating all these elements.

In addition to mapping all these things, the team also took photographs and drew some of the looted tombs and materials on the surface. For the intensive survey of the ten units, we wanted to estimate the original number of tombs, the rate of “success” of looters (distinguishing between barren/empty holes and actual looted tombs), and the range and numbers of grave goods abandoned by looters because they were broken, judged unsalable, or otherwise not valuable.

Outside of these ten sample areas, the team also recorded the number of tombs in the western half of the site, noting whether the tombs seemed to be constructed from boulders, wadi cobbles, or large slabs.

Part of our methodology was developed by an earlier, pilot project at neighboring EBA cemetery Bab adh-Dhra` in 2004. The shaft tombs at Bab adh-Dhra`’ have been looted intensively for decades, and we developed a method for mapping looting tombs and discerning barren looter pits. We also discovered the need for documenting looting at different scales since the damage to these sites is so vast.

We are currently working to compare our results of the intensive survey with what archaeologists discovered when they excavated about 10 tombs at Fifa in 1989-90. We hope to be able to gain a sense of what looters take, what they leave, and what has been lost archaeologically by the destruction of the site. Meredith is currently analyzing the field notebooks from the excavations to compare what we learned in 2011 with what they learned two decades ago before the site had been extensively looted.

Beginning in 2013 we (Chad and Morag) implemented an additional project – Landscapes of the Dead

Ethnographic Methods

Complementing the archaeological research, Follow the Pots uses ethnographic research methods, including interviewing all those with an interest in the region, the sites, the artifacts, and the artifacts collecting oral histories, visiting museums and antiquities shops, and examining the websites of online sales venues who sell these pots. Morag directs this arm of FTP, spending time in Jordan, Israel, Palestine, the UK, Canada, and the US talking with archaeologists, government officials, and residents of the southern Ghor, museum curators, collectors, looters, intermediaries, and antiquities dealers.

Ethnography is the study of living peoples today and is known by several other names: ethology, social anthropology, and cultural anthropology (depending on where one learns to be an anthropologist, the name changes). Conducting ethnographic research involves interviewing people who interact with these pots today (including looters and their family members, intermediaries, archaeologists, museum workers, government officials, collectors, and dealers) as well as seeking out the pots in antiquities shops, online auction houses (like eBay, Christies, or other online dealers), museums, and archaeological storehouses. Sometimes it is very easy to get people to talk about their relationship to these pots; other times it is very difficult.

Many people are familiar with gathering oral histories: Morag interviews people who worked with these pots or knew people who worked with the pots, in the past in any way, including looters, collectors, intermediaries, antiquities dealers, foreign and national archaeologists, local inhabitants, and government and museum officials. We learn a tremendous amount about how people used these pots in many ways in the past.

In talking with many different people involved with these sites and materials, she asks questions about how people think about these pots, if and how they think they are valuable in any way, and what people believe should happen with these archaeological objects.

We study the ceramic pots from the cemeteries of Fifa, en-Naqa, and Bab adh-Dhra`, located near the modern towns of Fifa, es-Safi, and Mazraa near the Jordanian shoreline of the Dead Sea. We examine how people use, sell, collect, or discard these archaeological artifacts to investigate people today’s ideas about the value of archaeological heritage as a resource in their daily lives. These pots were made and placed in graves of people who lived in the area 5,000 years ago. Approximately 60 years ago (Lapp 1965), people began looting the tombs in these cemeteries to collect and sell these pots in Amman and other markets. Archaeologists in the mid-twentieth century were drawn down to the Dead Sea region after seeing so many vessels for sale legally in Amman (prior to the 1976 Jordanian antiquities law) and Jerusalem, setting the stage for approximately 50 years of intensive archaeological research in the southern Ghor on Early Bronze Age and other historic and prehistoric cultures.

The people who originally made and used these pots as grave goods lived about 5,000 years ago (around 3,000 BCE) near the southern part of the Dead Sea. Archaeologists don’t know with certainty where these people lived: these cemeteries are not located near any settlements in the Dead Sea Basin. What this means is that we think that people living in the area (in towns, villages, farmsteads, and encampments) traveled to Fifa, Bab adh-Dhra`, and en-Naqa to bury their dead, but we can’t prove this interpretation yet.

So, whose pots are these today? This question of ownership today is the most important underlying idea guiding our research. Who owns these pots? Who should be able to use them and how should they use them? Who decides how these pots get used, and why do some people have more power and voice in deciding what happens to these pots? There are several ways to answer these questions, depending on who is speaking to us. The fact that different people have different answers to these questions draws us further down the pathways of following these pots. Under Jordanian law, these pots belong to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

This is a great, but somewhat, tricky question. In 1976 Jordan updated their antiquities law and in doing so they banned the legal trade in antiquities. Prior to 1976, the Jordanian Department of Antiquities licensed shop owners to sell antiquities, but in response to ongoing looting of archaeological sites and thefts from museums, the Jordanian government decided to outlaw the trade . In 1974 Jordan ratified the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property . In ratifying this Convention, Jordan agreed to abide by the principles outlined in the document and to aid other countries in preventing the illegal movement of archaeological objects. At the same time, other member states agreed to protect against the illegal importation of Jordanian material across their borders. Unfortunately, Israel is not a state party to the 1970 UNESCO Convention and they still have a legal market for antiquities (see Israel Antiquities Law of 1978 ), so looted pots from Jordan are often legally available for sale in Israel. One of the research goals of the Follow the Pots project is to try and figure out how these pots are crossing from Jordan into Israel.

The Early Bronze Age (EBA) is the term we use to describe the societies that lived in this region approximately 5,600-4,000 years ago (or 3,600-2000 BCE). For the very first time in this region, people built the earliest towns and cities with large fortification walls surrounding them. Thus, we link the EBA with the emergence of urbanism, or the invention of city life.

A great deal can (and did) change over 1,600 years with the rise and collapse of the first urban centers, and therefore the EBA is divided roughly into four sections based on the types of pottery and other goods that people made and used:

- EBA I (including IA and IB): 3600-c.3100 BCE

- EBA II: 3100-2800 BCE

- EBA III: 2800-2350 BCE

- EB IV (also called the Intermediate Bronze Age): 2,350-2,000 BCE

Fifa is a cemetery from the EB IA (the first half of the EB I period), en-Naqa a cemetery from the EB IA and early EB II periods. Bab adh-Dhra` has both a townsite (from early EB II to EB IV) and a cemetery (from EB IA to EB IV).

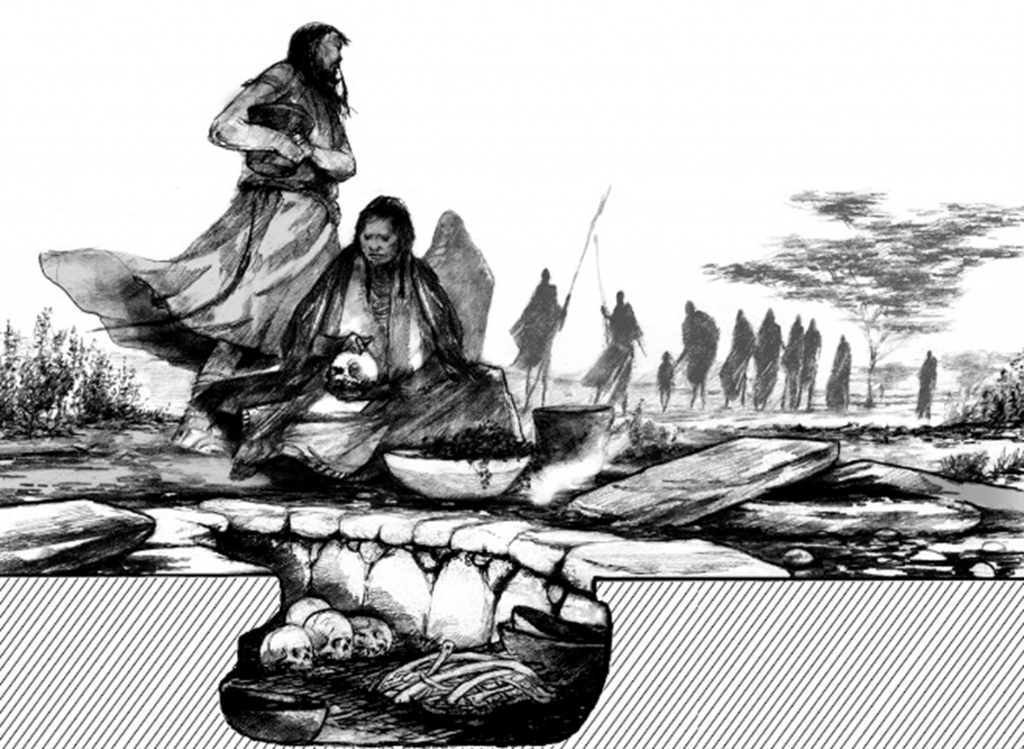

During the EBA people traveled to the site to bury their dead in secondary mortuary ceremonies. What this means is that people collected the bones of their dead, which had been buried elsewhere years earlier, traveled with these bones and grave goods to rebury the skeletal remains and the grave gifts in the cemeteries. The EBA IA people used cist tombs at Fifa and at en-Naqa, and they used shaft tombs (and later charnel houses) at Bab adh-Dhra`.

The cist tombs at Fifa were built by digging a pit, lining walls (and sometimes the floor) of the pit with stones, placing the dead persons’ remains in the chamber, placing a variety of grave goods with the deceased, and then sealing the chamber with large flat stone slabs.

Shaft tombs have a central circular shaft, dug 2-4 meters into the earth, and chambers excavated off the bottom of the shaft. Each shaft tomb at Bab adh-Dhra` had anywhere from one to five chambers for each shaft.

Mortuary practices are simply the steps that people follow when someone dies. The main difference between primary and secondary mortuary practices is the timing: primary rites occur in the few days after a person dies and people are preparing the body to be buried, while secondary mortuary practices occur long after a person has died. For mortuary practices to be considered secondary, some amount of time (weeks, months, or years) must pass before people visit, change, reopen, reorganize, or add to the grave.

Today in most places in the world, primary rites include preparing a body for funeral rites: washing, embalming, cremating, wrapping, and burying. During the days immediately following a death, any actions that involve the corpse and the mourners, such as wakes, prayers, visitations, grieving processions, or feasts by the body, are all considered primary mortuary rites.

Secondary mortuary rites occur long after the individual has died, taking place months or even years after the death. These include memorial feasts, replacing grave markers with newer versions, movement of a skeleton from its primary gravesite to a charnel house, or simply visiting the grave of the deceased. In many places secondary mortuary practices can involve many more people than the primary rites, since secondary ceremonies can be scheduled well ahead of time, allowing people to plan for a journey to participate.

In the case of Fifa, Bab adh-Dhra`, and en-Naqa, the EBA graves are overwhelmingly the result of secondary mortuary practices. When a person died in this region 5,000 years ago, they were most likely buried to allow their bones to deflesh (we don’t know where these primary graves were located since we don’t know where these people were living: another mystery to be uncovered through future research). After waiting several years, people dug up the bones of their dead to collect them for the journey to one of these cemeteries. Once at the cemetery, the EBA people built a tomb or open a previously used one and place the bones of their dead carefully in the tomb with grave goods that were deemed necessary and/or appropriate. They conducted whatever funerary rites were necessary, seal up the tomb, and then travel back to their homes and carry on with life.

Fifa (also spelled Feifa) is an archaeological site located near the southeastern shore of the Dead Sea in Jordan, south of the modern town of es-Safi. Archaeologists have identified four different times when people used the site (from oldest to most recent):

- the Pottery Neolithic (approximately 8,000 years ago), when people probably lived at the site on a small farmstead;

- the Early Bronze Age IA (about 5,000 years ago), when people buried their dead in a large cemetery;

- the Iron Age (about 3,000 years ago) when people built a fortified village on the highest part of the site, over the cemetery; and

- the modern-day, when people loot the 5,000-year-old cemetery to gather pots and sell them.

At the base of the promontory on which the ancient site of Fifa is located, sits a modern cemetery, which is consistently used to bury the recent dead.

Follow the Pots focuses on the Early Bronze Age period when people buried their dead in the cemetery at Fifa and the modern period when people loot the EBA graves for pots for sale on the antiquities market.

We learned many useful and interesting things in the 2011 season. One of the most important lessons we took away from the field was that every looter pit does not equal a looted tomb. This observation means that if we try and use Google Earth or aerial photographs to monitor and estimate numbers of looted tombs, we cannot equate robber pits with looted tombs. Instead, aerial photography must be paired with an on-the-ground survey, what archaeologists call groundtruthing.

We also confirmed what most archaeologists already know and fear: that archaeological research often paves the way for the looting of sites. While we were in the field, previously unlooted and surveyed areas of Fifa were looted at night. Our surveying and recording of the site in the Winter of 2011 brought the site to the attention of locals, who wondered what we were doing. They visited the site after the end of our field day and overnight looted two cist tombs, destroying the slabs, and possibly recovering artifacts.

We also gained a much better sense of who were the local stakeholders, including people directly involved in the antiquities trade and archaeology in the southern Ghor and those whose lives are not touched by these pots. We want to know how people use these sites and these materials, and what they think should or could be done with them. Every time we go into the field we strive to gain and maintain the trust of all these stakeholders, and we work diligently to honor that trust by nurturing personal relationships with everyone involved in the project.

We don’t know who buried their dead here, since there are no settlements nearby to the cemeteries. The nearest villages and towns were located about 30 km to the east and west, as the crow flies. Answering this question remains one of the most important future research projects that we may develop, depending on time and staffing. One of the best ways that we might be able to track the origins of these people would be to analyze the chemical composition of the clays in the pots and compare that to the clay sources still located throughout the region. If we can determine where the clay came from people used to make these pots, we would be much closer to determining where they lived.

There are several reasons why we have focused on Fifa for the archaeological portion of Follow the Pots:

- Of the three EB IA cemeteries in the southern Ghor of Jordan, Fifa has been the cemetery left undisturbed for the longest. The earliest looting of EB tombs in the region started at Bab adh-Dhra` in the mid-20th century, followed by en-Naqa, where looters began intensively working in the 1980s and 1990s. We know from working in the region for the last several decades that looters did not turn their attention to Fifa until 1990 after archaeologists conducted test excavations at the site. Once the site was identified and tested by archaeologists, locals knew that Fifa was another source for these grave goods.

- Fifa also is a relatively small (about 6.4 hectares, or 15.8 acres) cemetery, and contains graves from only the EB IA period and no associated settlement (yet identified). Both Bab adh-Dhra` and en-Naqa cemeteries are much larger and contain graves from more than the EB IA. For instance, the cemetery at Bab adh-Dhra` extends to the west where it blends into a later Byzantine and Roman cemetery (Qazone), making it difficult to determine the specificity of intentions of the looting: did looters set out to collect EBA pots or Byzantine materials? Or were they looking for any kind of grave good they could find? By limiting our archaeological focus to Fifa, where many of the looters are actively working, we can talk to people specifically about why they take certain objects from the EBA tombs and not others.

- Finally, as part of the larger research task of publishing the results of excavations at many of these sites, we needed to survey the site to produce a proper topographic map of the site of Fifa, noting all the archaeological remains that we can see today on the surface. By archaeological remains, we mean all the walls, tombs, trenches, and even modern disturbances to the site. Modern disturbances at Fifa include military slit and tank trenches from the 1960s and 1970s military encampments, as well as looters’ trenches and bulldozer cuts from building on or near the site.

These pots began their lives as grave goods, placed with the long-dead in cist or shaft tombs. For this reason, we think of their first lives as devoted to accompanying the dead.

When archaeologists or looters remove pots, stone maceheads, shell bangles, or other materials from these tombs, they propel these objects onto a new pathway, into a new life. If the objects are broken or are undesirable to collectors, they remain strewn across the site in spoil heaps until the weather or other forces break them down slowly. Looters generally avoid keeping shells, shell bracelets, beads, and human skeletal remains, and so their second life is one of slow submission to the elements.

Looters do take away whole pots, stone maceheads, and stone vessels to be delivered to intermediaries, who often send them to free ports to be laundered (with the forgery of provenience papers). Once laundered, they are distributed throughout legal and illegal channels to be sold to collectors through the Internet and Brick-and-Mortar stores. In some cases, we have found that stone bowls often were given as gifts to people in Jordan, and thus some of these items will never enter the market at all and therefore have never been issued false provenience papers. Ultimately, they come into the hands of collectors, and the new life of these objects may involve display in homes, educational institutions, museums, and offices. Often the pots are associated with stories of how and why people acquired them, or how people value them (as a memento of a journey, as a “touchstone” with religious beliefs, as gifts from others, as inheritances from family members, or as pieces of art).

Like looters, archaeologists also remove these materials from the tombs. However, we remove everything, broken or whole, take notes on the location of these objects, and dedicate a great deal of time documenting through photography, note-taking, and drawing the context in which we find these objects. Legally we hold permits from the Jordanian government to excavate, and we are obligated to store, or curate, these materials for future scientists. In some cases, we may also be obligated to develop museum displays to exhibit these pots to the public for educational purposes. These grave goods start their second lives as objects in museum display cases, storage cabinets, and as objects of scientific inquiry. In the case of the EBA materials from Fifa, Bab adh-Dhra` and en-Naqa, archaeologists use these objects to tell stories about the beginning of urban society, life in early cities, the emergence of social hierarchies, and how people bury their dead in secondary mortuary rituals. Through time, materials on the looting and archaeological pathways may be reborn yet again, as they are sold or moved, and used and valued differently and in new places.

Morag M. Kersel (Associate Professor at DePaul University) is a dual Canadian and American citizen who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge in the UK. Dr. Meredith S. Chesson (Professor at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana 100 miles from Chicago) is an American who earned her Ph.D. at Harvard University in the US. Dr. Austin (Chad) Hill (a postdoctoral research at the University of Pennsylvania) is an American who earned his Ph.D. at the University of Connecticut.

We are all field archaeologists who have worked in Jordan and Israel for many years on many different archaeology projects, as well as on projects in Canada, Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Palestine, and the United States. For more information about Morag, Chad, and Meredith, please visit their university homepages:

https://anthropology.nd.edu/faculty-and-staff/faculty-by-alpha/meredith-chesson/

https://anthropology.sas.upenn.edu/people/austin-chad-hill

https://las.depaul.edu/academics/anthropology/Faculty/Pages/morag-kersel.aspx

We use different research tools to follow the pots: aerial photography, surveying, archaeology, ethnography, archival research, and oral histories. The pots are easily recognizable to archaeologists familiar with Early Bronze Age pottery. Their shapes, sizes, decorations, and fabrics (the mix of clay with small bits used to make the pots) are all distinctive, so it’s easy to spot these pots (or their fake counterparts) in stores, museums, and in online auction sites.

Currently, much of the archaeology portion of our research occurs in our university offices: we are comparing the excavation notes and photographs from Fifa excavations in 1989-1990 to the results from our 2011 survey at Fifa, in which we used surveying equipment to map the cemetery of Fifa and recorded information about robbed tombs and grave materials left scattered on the surface of the site. By comparing what archaeologists discovered during systematic excavations of unlooted tombs with what we found scattered on the site surface in 2011, we hope to understand what looters take from the site (what they can sell or give away) and what they leave (what holds no value for them at all). Meredith leads this aspect of the project since she is working with the original field notebooks to write up and publish the final report from these earlier excavations.

Morag is conducting the ethnographic and oral history research programs and with Chad the archaeological survey of the site. Many people are familiar with gathering oral histories: Morag interviews people who worked with these pots or knew people who worked with the pots, in the past in any way, including looters, collectors, intermediaries, antiquities dealers, foreign and national archaeologists, local inhabitants, and government and museum officials. We learn a tremendous amount about how people used these pots in many ways in the past. Ethnography is the study of living peoples today and is known by several other names: ethology, social anthropology, and cultural anthropology (depending on where one learns to be an anthropologist, the name changes). Conducting ethnographic research involves interviewing people who interact with these pots today (including looters and their family members, intermediaries, archaeologists, museum workers, government officials, collectors, and dealers) as well as seeking out the pots in antiquities shops, online auction houses (like eBay, Christies, or other online dealers), museums, and archaeological storehouses. Sometimes it is very easy to get people to talk about their relationship to these pots; other times it is very difficult.

In cooperation with the Jordanian Department of Antiquities under the umbrella project of Follow the Pots, the Landscapes of the Dead Research Project is using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs, ‘drones’ – Chad’s specialty) to monitor archaeological site looting at the Early Bronze Age site of Fifa in Jordan. Drones, both fixed and rotary-wing, are being deployed as part of a multi-year study of the scale and pace of looting at the site. By constructing high-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) across multiple years, we can both map the site and identify new looting events from year to year.

Because looting of archaeological sites, selling antiquities, or buying antiquities is illegal in most countries, many of the people who interact with these pots may be involved in criminal activity, regardless of intentions and knowledge or ignorance of international standards established by UNESCO in 1970 (see this link for more information on this convention).

Some people are willing to talk with us, regardless of associated illegal elements, because we follow an ethical set of guidelines for anthropologists who work with living peoples. This ethical standard was developed in the US in 1974 and is known as the Belmont Principles (see the Health and Human Services website for more information). The Belmont Standards have three basic ideas that anthropologists must fulfill to work with people today: Beneficence, Justice, and Autonomy. Here’s what it boils down to:

- We are obligated to ensure that we do no harm by implicating a person who talks with us about illegal activities and to ensure anonymity. We record no names and/or identifying information, and we do not require anyone to sign consent forms and keep all interviewing data in a secure place;

- We clear all the transcripts of interviews with people by providing them written transcripts of interviews, so they may redact portions or all the information covered in the interview;

- Any person who talks with us may withdraw from the study at any point, and they take their information (given to us in interviews) with them—we will not use what we have learned in any presentations, publications, or overall analysis;

- We expressly do not use a “good guys-bad guys” approach to our work—we’re not interested in judging people or identifying criminals. In fact, we think about looters and archaeologists as very similar, in that we all dig up artifacts and use them in particular ways outside of their original context; and

- Ultimately, we want to be able to serve the local communities in the Southern Ghor and to discover the ways in which local archaeological heritage can make meaningful contributions to their lives, such as in helping them to weather the economic crises they face in Jordan today.

We find pots in many places, some expected and some surprising, depending on the legal or illegal nature of their pathways from grave to current location. In Jordan, it was legal to sell and purchase these pots before 1976, and therefore thousands of pots were purchased by tourists, museums, and collectors. Institutions, like museums, universities, and research organizations, often kept records of these purchases and we can track the pots through these records. For example, we have traced Bab adh-Dhra` pots purchased legally to the Vatican, the British Museum, the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, and to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. In other cases, institutions who helped to fund the digs in the 1960s and 1970s often received pots for their collections, and the main institutions (Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the Smithsonian Institution) that sponsored the Expedition to the Dead Sea Plain [EDSP] hold large collections of these pots and other tomb materials still being studied or curated on permanent loan from Jordan. Many of these pots still reside in museum and archaeological storerooms in Jordan and part of this project is also to document the whereabouts of tomb groups in Jordan.

Beyond these legal pathways, many of these pots find their way to legally licensed antiquities shops in Israel, mostly in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. While it is nearly impossible to prove or track how the pots came to these shops today, it is very likely that there were looted illegally in the recent past, laundered with new manufactured papers of provenience (archaeological findspot – see FAQ on definitions of provenance and provenience), and then sold to shops for legal sale to tourists and other collectors. Looters have supplied the antiquities market in Jordan and other countries for decades. We find Early Bronze Age pots from the Dead Sea Plain listed for sale on internet auction houses, in licensed antiquities shops in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and in private homes of people who traveled as tourists to Jordan or Israel. Often the keywords used in online sales reference the Holy Land, or the Patriarchs/Matriarchs, Abraham, Sarah, or Ancient Palestine, to attract customers who are keen to purchase a small piece of religious memorabilia from the region of the world so important to the development of Judaism and Christianity. Tourists visiting the Holy Land often may also be attracted to signs in licensed Israeli shops advertising pots from 4,500-5,000 years ago, due to the traditional connection between the southern Dead Sea region and the Biblical sites of Sodom and Gomorrah. We look for these clues to track down examples of these pots on the antiquities markets worldwide.

The ruins of the fortified town of Bab adh-Dhra`, as well as those of the Numayra (13 km to the south), have traditionally been associated with the Biblical stories of Sodom and Gomorrah (Rast 1987). The Biblical story of these two cities focuses on their destruction by God’s wrath as part of the greater story of Lot and his daughters (Genesis 19). While there is no archaeological evidence at these sites to confirm these stories, many visitors to the region today visit Bab adh-Dhra`, drawn to the southern Ghor by the Biblical stories. Therefore, the pots from the cemetery at Bab adh-Dhra`, as well as from the neighboring cemeteries of en-Naqa and Fifa, can carry with them this association.

We’re keenly interested in talking with people who have bought these pots to learn more about why they bought them, how they enjoy or use them today, and what possessing these pots means to them. If you’ve seen any of these pots in stores or museums, or have purchased them as souvenirs, we’d be thrilled to chat with you about how these pots fit into your life. You can contact us at our university offices or by email (mchesson@nd.edu or mkersel@depaul.edu or chadhill@sas.upenn.edu).

Looters rob archaeological sites for a variety of reasons, and often we can’t identify only one motivation (see Kersel 2008). Our research has documented that in the areas surrounding Fifa, en-Naqa, and Bab adh-Dhra` there is a very long history of looting tombs, from at least the 1950s onward and likely from before that time. Generations of kids have watched, or have helped, their family members and neighbors loot sites, and there can be an economic reward for selling looted pots and other items to intermediaries. In times when the country of Jordan faces tremendous challenges of poverty, conflict, and rapid population growth (especially from refugees from the wars in neighboring regions), the people of the southern Ghor often suffer from food shortages and unemployment. Selling a pot or three can help a family feed their children, and perhaps give some sense of control over a frustrating situation that produces feelings of helplessness and even despair: even if one can’t find work as a day laborer in the fields, one can still bring in some money by robbing tombs to find whole pots. Looting is demand-driven.

Yes, they certainly do. While not as common as the pots, looters also find and take the stone maceheads and stone vessels sometimes placed in the tombs as grave goods. They don’t seem to care much for the shell bangles that people would have worn on their arms, and other small items (like beads, metal pins, or needles) also go uncollected. From our survey of the surface of Fifa, we found beads, chipped stone tools, small metal objects, and broken pottery, and stone objects that were left on the ground.

Collectors (and therefore the intermediaries and looters) focus on whole, unbroken objects like pots and stone bowls.

Since people have purchased pots from Fifa, en-Naqa, and Bab adh-Dhra` for at least 60 years, it’s not easy to narrow down the list of types of buyers. We do know that many of these pots have been, and continue to be sold, in licensed antiquities shops in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and that many religious and secular tourists visiting the region purchase these pots as mementos of their journey. Beyond those tourists who buy a pot to take home as a souvenir or religious touchstone, there are collectors who seek out these materials for their own collections or as investments, to be sold later. Pots from these sites are also for sale on eBay and other internet venues.

When collectors or antiquities dealers purchase large numbers of pots, the tomb groups sometimes come to light. For instance, one year a large department store in London displayed a large group of these pots as part of their holiday season sales. An archaeologist came into the store by chance and saw the pots for sale on a large display table and reported the situation to the store managers.

Museums and other research institutions can purchase these pots from antiquities dealers, and we can trace these purchases with the museum acquisition records. Often these pots have been laundered and given false papers of provenience. What this means is that intermediaries, who purchased the pots from the looters, falsify papers that state that the pots were collected before the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property and the 1976 Jordanian Law and thus appear to have been acquired legally.

Provenience is the archaeological find spot of an object – the actual place that an item was found archaeologically. Provenance is the full ownership history of an object, which includes the provenience of an object.

The two terms are used differently in different parts of the world and in different academic disciplines but are sometimes used interchangeably. Art historians tend to use the word provenance, while archaeologists use the word provenience. Art historians and museums tend to stress the importance of provenance, based on a long history of collecting art objects and tracing the life history of a piece of art from artist to collector through time. For an archaeologist, they also link provenience, the physical location in space and time, to the concept of context. Context involves the physical, geographical, and social environment in which people used or made any object. For most archaeologists, we stress the importance of context for understanding how an object was used and what ideas, values, and meanings people placed on any object. When objects are looted, like the pots from the graves in the Dead Sea area, they are removed from their original context and therefore we lose information about people and their lives and deaths in the past.

Many archaeologists, conservators, and museum professionals feel very uncomfortable answering this question, since it requires us to assign monetary values to these pots: many generally consider all artifacts, sites, and ancient landscapes to be priceless. However, we can track the value of these pots by talking with dealers, collections, and by checking online sites and auction catalogues where these pots are sold. Currently, the pots sell for anywhere between $150-300 USD depending on their decoration, size, condition, and provenance.

A stakeholder is an individual or group with an interest in a group’s or an organization’s success. Stakeholders can and do influence programs, products, and services. Stakeholders related to Follow the Pots are those individuals and/or institutions who have an interest in the movement of Early Bronze Age pots from the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan. This includes, but is not limited to dealers, archaeologists, collectors, looters, local Jordanians, tourists, government employees, museum professionals, heritage practitioners, and lawyers.

UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation, is a specialized agency of the United Nations system. The organization was created more than a half century ago, with the mission to build the defenses of peace in the minds of men. For the purposes of Follow the Pots the UNESCO Conventions of 1970 and 1972 are most relevant.

Yes, there certainly are. Here is a short, and certainly incomplete, list of websites from Community Archaeology Projects in Jordan.

Much of our research into the various lives of pots from the Early Bronze Age cemeteries along the Dead Sea Plain is informed by the influential work of Arjun Appadurai (1986) on the social lives of things. We are fascinated by the lives the pots have lived as:

- Grave goods buried with various Early Bronze Age individuals

- Excavated archaeological artifacts that were part of scientific excavations.

- Looted artifacts that are highly prized by individuals – visitors to the area, tourists, contractors etc…

- Collected objects – on a mantelpiece, in a museum exhibit, or in the classroom as an educational tool.

We consider all these lives of equal interest.