Follow the Pots

1978 Tomb Group Distribution

Marly Prom and Morag M. Kersel

The Early Bronze Age site (3600-2000 BCE) site of Bab adh-Dhra` and its neighboring ancient town of Numayra (located 13 km south) have at times been associated with the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, sites immortalized within the pages of the Bible (Albright 1924). The Biblical stories of these two cities revolve around their destruction by the wrath of God as part of the larger story of Lot, his wife, and their daughters (Genesis 19). While there is no archaeological evidence to confirm any connection between the ruins of Bab adh-Dhra` and Numayra (see Chesson 2020) and the Biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, the legends persist and many visitors to the region are drawn to these sites and the artifacts from the bible. Due to this biblically-based interest, grave goods (ceramic vessels) buried with ancient ancestors at the cemeteries at Bab adh-Dhra’, en-Naqa, and Fifa, are in high demand. Unfortunately, this demand leads to looting at these archaeological sites. Bab adh-Dhra’ archaeologically identified as an ancient townsite with an associated cemetery includes a great wealth of Early Bronze Age artifacts.

At the Early Bronze Age (3600-2000 BCE) cemetery at Bab adh-Dhra’, local inhabitants of the Dead Sea Plain buried their dead in shaft tombs and charnel houses (buildings built specifically to house human remains, see Chesson 1999). Burials include a standard set of grave goods: ceramic vessels, carnelian beads, basalt bowls, lambis shell bracelets, limestone maceheads, flint tools, and the occasional bronze item (Kersel and Chesson 2013a).

The remnants of mortuary practice are an integral part of the archaeological record providing information about ancient ancestors and their lives. Unfortunately, since the early part of the 20th century, the cemetery at Bab adh-Dhra’ has been the object of systematic and sustained looting due to the unbridled demand for EBA pots from these cemeteries associated with the Bible (Kersel and Chesson 2013a). In the late 1950s, Lapp, an archaeologist and director of the Jerusalem School of the American Schools of Oriental Research (now, the W. F. Albright Institute for Archaeological Research), noticed a trickle, a stream, and then a flood of Early Bronze Age pots in the Jerusalem antiquities market (Lapp 1968; Saller 1964-1965).

In 1965 and 1967, in response to the looting of so many valuable archaeological items, Dr. Paul Lapp, led expeditions to Bab adh-Dhra’ to excavate the heavily damaged cemetery (Kersel and Chesson 2013a; Kersel and Greenland 2017; Kersel in 2019). During the 1965 and 1967 field seasons, the team excavated thousands of artifacts, including the pots that are the namesake of this project. Before he could return to Jordan to continue his work, Paul Lapp died tragically while swimming off the coast of Cyprus in 1970, leaving his wife and fellow archaeologist, Nancy Lapp with the task of analyzing and publishing the data from his earlier excavations. It also left Nancy and the Jordanian Department of Antiquities [DoA] with a predicament of storing 1000s of pots from the various shaft tombs and charnel houses (see Kersel 2015a).

This question of what to do came to a boiling point in the mid-1970s when new excavations at Bab adh-Dhra’ were initiated by archaeologists Dr. Walter Rast and Dr. R. Thomas Schaub (who both worked with Lapp at the earlier excavations).

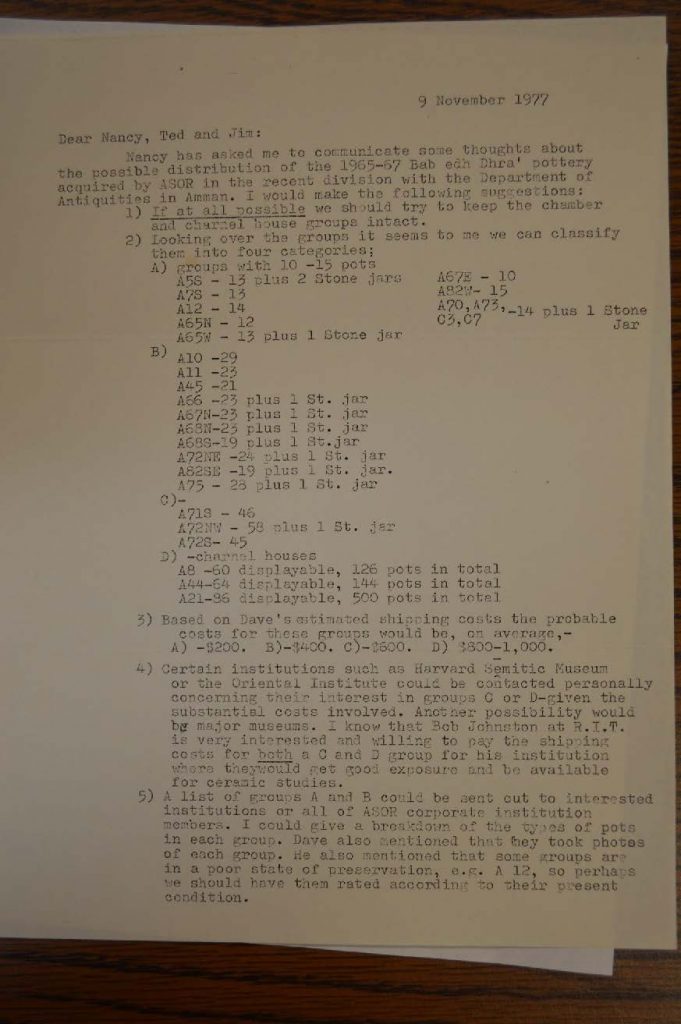

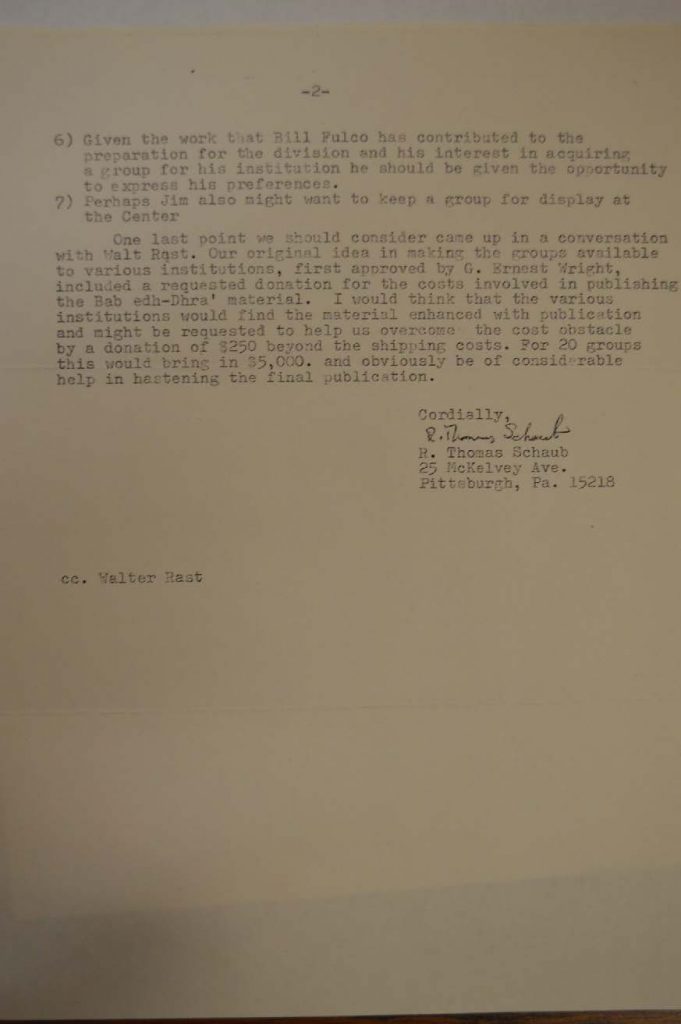

The additional finds from the Rast and Schaub expeditions created even greater stress on the already limited DoA storage space. An inspired solution was required. The Jordanian Department of Antiquities, the American Schools of Oriental Research [ASOR], the sponsors of the original Lapp excavations, and Nancy Lapp developed the idea to sell the Lapp artifacts to ASOR member institutions for hands-on teaching, research, and display. In a letter between Nancy Lapp and the ASOR Board outlining the proposal, she writes, “There is reason to think that this unusual proposal will be picked up! It could mean that a group of 8 or 10 complete or fully reconstructed pots could be available for roughly $150, delivered directly to a museum” (Nancy Lapp to the ASOR, 1 September 1977, Nancy Lapp correspondence). Before the pots were distributed, Thomas Schaub sent a letter to Nancy about the best ways to divide the tomb groups.

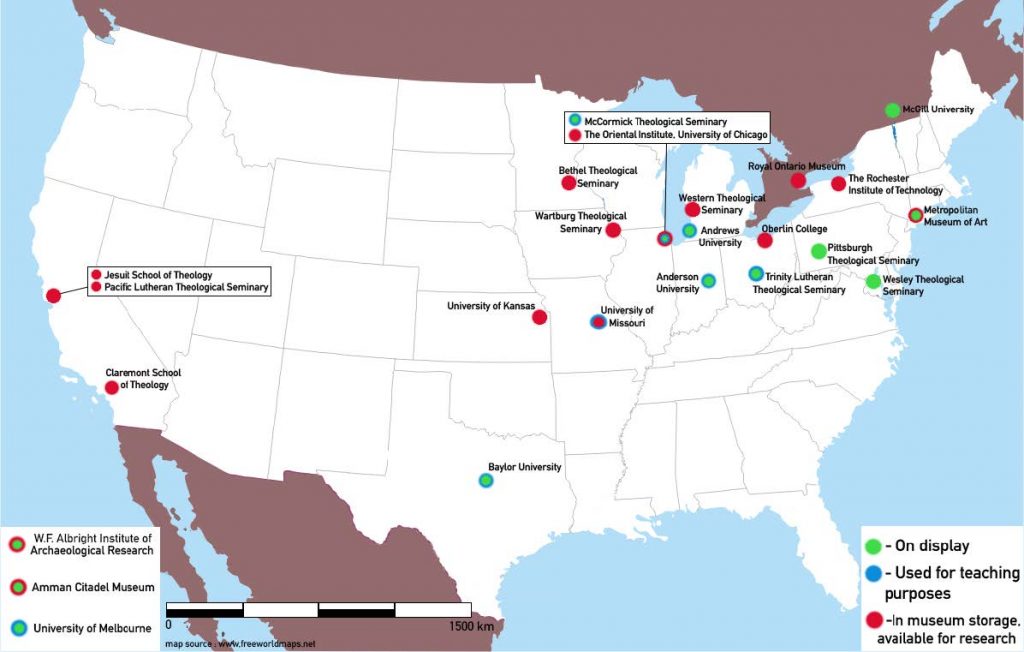

This process narrowed down the different sizes of each tomb group to help universities and institutions identify which groups they wanted. Institutions were successful based on a broad regional distribution, although many were smaller seminaries located in the American Midwest.

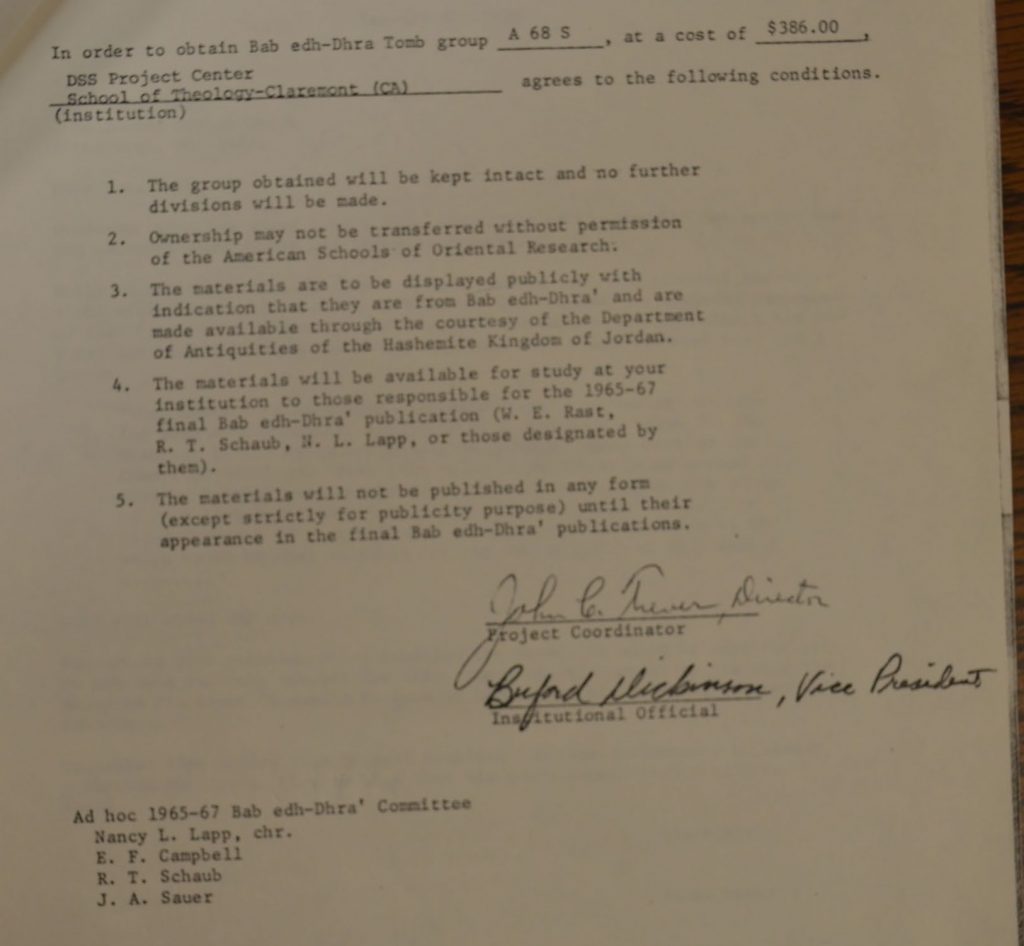

A specific set of conditions would ensure their display and educational use.

- The groups will remain intact with no further division without the permission of ASOR, thus ensuring that ASOR and the Department of Antiquities would be able to keep accurate records of the location of the Bab adh-Dhra ‘material.

- The pots should be displayed publicly with proper

- They should be available for study by those responsible for the publication of Bab adh- Dhra‛. This would ensure that Schaub and Rast, who were working on the publication of the results of the 1965–1967 Lapp investigations (Schaub and Rast 1989), had the necessary access to the collections.

- The “charge” for the collection should be paid in full promptly (Nancy Lapp to ASOR Representatives of Institutional Members, 26 December 1977, Nancy Lapp correspondence).

The Jordanian government agreed to this system of state-sanctioned sale of archaeological items from Jordan, as it would increase interest in the archaeology, people, and places of Jordan. At the same time, this arrangement would strengthen the relationship between Americans and Jordanians. The objects were to act as ambassadors on behalf of Jordan (Adnan Hadidi, the director of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, to Nancy Lapp, August 15, 1977, Nancy Lapp correspondence). For anywhere between $100 and $1,500, eligible ASOR member institutions were offered tomb groups from chambers and charnel houses (Kersel 2015a).

Twenty-four institutions received tomb groups; a further fifteen were unsuccessful in their bid for a group (Kersel and Greenland 2017). The system of legal purchase also alleviated any issues of provenance and objects without a secure backstory related to the ownership of these items.

1,186 pots ($6 per pot) and 10 basalt bowls ($25 for each basalt bowl) were distributed throughout Australia, Canada, and the United States. Generating almost $14,000 in income ($51,824 adjusted for today’s dollar value), proceeds from the pot allocation would be used for future publication and excavation at Bab adh-Dhra‛, small projects conducted by the American Center of Research, an American archaeological research institution based in Amman, and other ASOR initiatives.

Since 2011 The Follow the Pots Project has been tracking (this is a work in progress) these Early Bronze Age tomb groups to assess if they are in their original distribution location, on display, and if they are being used for educational/research purposes.

1978 Location of Original Sale

- Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, Jerusalem

- Amman Citadel Museum, Amman Jordan

- Anderson University, Anderson IN

- Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI

- Badè Museum of Biblical Archaeology, CA, USA

- Baylor University, Waco TX

- Bethel Theological Seminary, Paul, MN

- Jesuit School of Theology, Berkeley CA

- McCormick Theological Seminary, Chicago IL

- McGill University, Montreal PQ

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

- Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH

- Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Pittsburgh, PA

- Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, ON

- School of Theology, Claremont CA

- The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, Chicago IL

- The Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester NY

- Trinity Lutheran Theological Seminary, Columbus OH

- University of Kansas, Lawrence KS

- University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

- Wartburg Theological Seminary, Dubuque IO

- Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington DC

- Western Theological Seminary, Holland, MI

This information was compiled by M.M. Kersel (one of the FTP project PIs), Marly Prom (research assistant supported by the DePaul University URAP awards), Julian Hirsch of Oberlin College, and the students of ANT 256 – Old World Material Culture (Winter 2018).

References

Albright, W. F. 1924. The Archaeological Results of an Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea. BASOR 14: 2–12.

Chesson, M.S. 1999. Libraries of the Dead: Early Bronze Age Charnel Houses and Social Identity at Urban Bab edh-Dhra‘, Jordan. JAA 18: 137–64.

———. 2001. Embodied Memories of Place and People: Death and Society in an Early Urban Community. In M.S. Chesson (ed.) Social Memory, Identity, and Death: Anthropological Perspectives on Mortuary Rituals. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, pp. 100-113. VA: American Anthropological Association.

———. 2015. Reconceptualizing the Early Bronze Age Southern Levant without Cities: Local Histories and Walled Communities of EB II–III Society. JMA 28: 21–79.

Hirsch, J. 2017. Winter Term 2017 Part 2. Bab edh-Drah Project https://trowelsarefun.wordpress.com/2017/01/29/winter-term-2017-part-2-bab-edh-drah-project/

Kersel M.M., 2015a. Storage Wars. Solving the Archaeological Curation Crisis? Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 3(1): 42-55.

———. 2015b. An Issue of Ethics? Curation and the Obligations of Archaeology. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 3(1): 77-80.

———. 2019. “Itinerant Objects. The Legal Lives of Levantine Artifacts.” In A. Yasur-Landau, E. Cline, and Y. M. Rowan (eds). The Social Archaeology of the Levant, pp. 594-612. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kersel M.M. and M.S. Chesson, 2013a. Looting Matters Early Bronze Age Cemeteries of Jordan’s southeast Dead Sea Plain in the Past and Present. In S. Tarlow and L. Nilsson Stutz (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial, pp. 677-694. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2013b.Tomato Season in the Ghor es-Safi – A Lesson in Community Archaeology. Near Eastern Archaeology 76(3): 158-164.

Kersel, M.M. and F. Greenland, 2017. Objects on the Move. The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. The Oriental Institute News & Notes 233 (Spring): 10-13.

Lapp, P. 1966. The Cemetery at Bab edh-Dhra‘, Jordan. Archaeology 19: 104–11. Saller, S. 1964–1965. Bab edh-Dhra‘. LibAnn 15: 137–219.